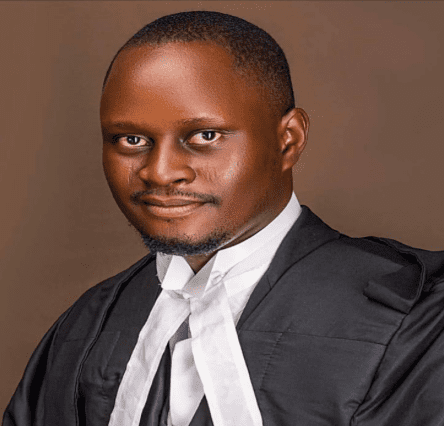

“The future arrived before the law was ready and now the law is racing to catch up.” That was the first line tech-law expert Kabir Adeyemo dropped as he settled into a panel discussion last week, and the room instantly leaned forward. For many, autonomous systems are dazzling proof of human innovation; for Kabir, they are also ticking legal puzzles waiting for clarity. And as he began to unpack the issue, one thing became clear: the world is only beginning to understand what it means to hand decision-making over to machines.

To him, autonomous systems ranging from self-driving cars to algorithmic decision engines used by governments and corporations may promise efficiency and safety, but they also reveal troubling gaps in global legal frameworks. “People think the biggest challenge is whether the technology works,” he said. “But the real challenge is whether the law works around it.” He reminded the audience that one of the earliest international documents forced to confront this shift was the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic (1968). The Convention originally insisted that every vehicle must have a human driver in control. But in 2016, as Tesla, Waymo, Baidu and others pushed boundaries, member states amended it to allow automated driving systems so long as human override remained possible. “That amendment,” Kabir observed, “was the first official signal that international law was willing to coexist with autonomous intelligence.”

Still, among the many puzzles autonomous technology raises, one question continues to dominate legal circles: When an autonomous system makes a decision that causes harm, who is responsible? He laid out the dilemma plainly. It could be the manufacturer, if the underlying design was faulty. It could be the software developer, if the algorithm behaved unpredictably. Or it could be the user, if warnings were ignored or systems misused. The issue is far from theoretical. He recalled the 2018 fatal crash involving an autonomous Uber test car in Arizona, a tragedy that forced regulators worldwide to confront an uncomfortable truth: when the driver is a machine, accountability no longer follows familiar patterns. “That incident,” he said, “forced regulators to acknowledge that the courtroom is no longer the same.”

Across the world, different regions are trying to regain control. Europe remains the most determined. The newly adopted EU Artificial Intelligence Act categorizes autonomous systems as high-risk technologies and mandates transparency, human oversight, and strict risk assessments. “It’s the closest thing the world has to a blueprint,” he remarked. “And trust me other regions are watching.” On the technical front, UNECE’s WP.29 has already issued binding regulations on automated lane-keeping, cybersecurity, and over-the-air updates rules now shaping vehicle standards in more than sixty countries. These guidelines, Kabir hinted, form the quiet but indispensable backbone of emerging autonomous mobility regulation.

But the conversation, he insisted, must stretch beyond cars. AI-powered decision engines already evaluate loan applications, screen job seekers, predict crime, assess asylum claims, and determine welfare eligibility. “These systems,” he said, “make decisions that shape human lives every day and most people have no idea they’re interacting with an algorithm.” With global treaties still catching up, the world has turned to soft-law frameworks. He referenced the OECD Principles on AI (2019), which encourage human-centered, accountable, and transparent AI capable of being audited when failures occur. He noted the UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of AI (2021) endorsed by 193 countries, for its bold insistence on fairness and its warnings against discriminatory or opaque automated systems. And he pointed to the Council of Europe’s Draft Framework Convention on AI (2024), the closest attempt at a binding treaty, aiming to anchor autonomous technologies to human rights, democratic values, and cross-border accountability. These instruments, he said, form the moral surface upon which future global AI law will likely be built but they lack the sting of enforceability. “Guidelines don’t bite,” he cautioned, “and when an algorithm denies someone housing or flags them as a security risk, guidance is not enough.”

Attention then shifted to another growing concern: the sheer influence of leading tech companies Google DeepMind, OpenAI, NVIDIA, Amazon, Tencent, whose systems often evolve faster than governments can regulate. “Corporations now influence the rules more than governments,” he observed. “And that creates a geopolitical tension between innovation and sovereignty.” He recalled recent warnings from the UN Secretary-General about autonomous weapons systems machines capable of identifying and engaging targets without human input. The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) is still debating meaningful global rules, but no consensus exists.

To Kabir, the world is inching toward a moral crossroads. “What happens when autonomous decision engines start making moral judgments?” he asked. “Who gets to encode the values of an entire society into a machine?” For him, the answer must lie in global cooperation. Nations share the same digital ecosystem and a regulatory gap in one country can rapidly become another’s crisis.

As he brought his analysis to a close, Kabir offered a sober reminder. “Autonomous systems are not the problem,” he said. “The problem is believing that innovation can replace responsibility.” He argued that the law must evolve not to slow progress, but to ensure humans remain the center of their own technological future. And in a world where machines increasingly make decisions once reserved for people, his final words rang with quiet urgency: “If we want a safe future, then autonomy must come with accountability.”