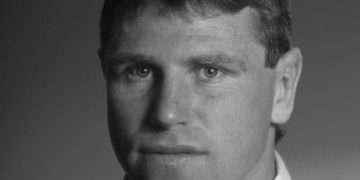

Why have the Mirror and Guardian both apologised and paid privacy damages to former GB News presenter Dan Wootton, many might wonder?

Their reports were true, and pertained to criminal allegations about a prominent right-wing media figure – so of huge interest to their readers. (Two police investigations against Wootton have since been discontinued.)

But the UK has a developing judge-made right to privacy which is creeping in its scope and which the publishers were fearful of having to argue against in the High Court.

It is the sort of story Wootton himself might have written in his time as a showbiz journalist at The Sun and News of the World, but which he now views to be beyond the pale (in what he admits is a major change of heart).

In 2018, Wootton wrote an article for The Sun with a headline describing actor Johnny Depp as a “wife-beater”. Depp sued for defamation and lost in 2020 when the judge ruled the article was “substantially true”.

In an apology written for his new Substack newsletter, Wootton said he now believes that Sun column was a breach of privacy that he regrets. And, whether the allegations were true or not, if such a column appeared today and Depp sued for breach of privacy he might well win.

Wootton’s argument that reporting by The Sun and Mirror breached his privacy centres around a February 2022 Supreme Court judgment that ruled news service Bloomberg breached the privacy of a businessman by publishing the contents of a confidential letter that revealed he was the subject of criminal complaint.

The court ruled that when someone is under criminal investigation they have a right to privacy until the point at which they are charged.

The UK law of privacy is judge-made because it is up to the courts to balance everyone’s right to privacy under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights versus journalists’ right to freedom of expression under Article 10. Any invasions of privacy must be justified in the public interest.

Why did The Sun, Mirror and others identify Wootton in the first place?

The Wootton case was different from Bloomberg because allegations against him had already been put in the public domain by Byline Times several months earlier and very widely discussed on social media.

Wootton himself then spoke about the allegations on GB News when he admitted to “errors of judgment” but said that “criminal allegations” against him were “simply untrue”.

In October 2023, Byline Times revealed that Wootton was the subject of a police investigation after this was confirmed by the Met Police.

College of Policing Guidelines state that the force cannot name suspects before charge in anything other than exceptional circumstances. But on this occasion, as with some other high-profile cases, the Met confirmed it was a conducting an investigation into an unnamed individual who journalists were then able to identify.

This revelation from Byline Times was repeated by The Mirror, Guardian, The National and numerous individuals on social media.

The publishers may have assumed it was safe to report on this breaking story because the fact that Wootton was subject to criminal allegations was already in the public domain and because the Met Police had confirmed he was under investigation.

Why have Sun and Mirror paid Wootton damages?

The Sun, Mirror and The National took their stories down after being contacted by a lawyer for Wootton who explicitly cited the Bloomberg precedent. Given that all the reporting on this story has been carried out by Byline Times, which reported extensively on the Wootton allegations, the other publishers may have decided that this was not their fight to win.

Byline Times may yet feel it has enough material to mount a public interest defence, but other publishers who followed the story up rather than backing it up with first-hand reporting might feel on shakier ground.

For the Mirror and Guardian, litigation fatigue may also be a factor. The Mirror is still engaged in wide-ranging and expensive legal actions related to hacking. The Guardian is fighting a £10m defamation claim from the actor Noel Clarke who was accused of sexual misconduct. Given the huge expense of fighting defamation and privacy actions where legal fees can run into the millions, publishers must be pragmatic about how many cases to take on.

The apologies from the Mirror and The Guardian were accompanied by contributions to costs believed to be in the order of low five figures.

Ultimately the Wootton case may lie in a grey area on privacy but it will be a risky and expensive point to prove for any publisher brave enough to take him to court. Byline Times has made no indication so far that it is prepared to settle.

Before Cliff Richard’s 2019 privacy win against the BBC it was not unusual for criminal suspects to be named at the point of arrest. This went on throughout the hacking scandal and Operation Elveden, for example, each time a new journalist was questioned by police.

Openness versus secrecy

Those who argue for openness fear secrecy around arrests and investigations could lead to less scrutiny of the police. Some are concerned about the prospect of people being arrested and being held at police stations with no public right to know what has happened to them.

The other argument in favour of disclosure is that secrecy could protect wrongdoers. There have been cases where publicity at the point of arrest has led to more victims coming forward.

In cases like Wootton, where allegations have been widely publicised, it could be argued that the public have a right to know that police are taking claims seriously. Wootton would, of course, still have recourse to a defamation action if accusations were untrue.

In Northern Ireland, those accused of sexual offences have anonymity up until the point of charge for their lifetime and 25 years after their death after new legislation was introduced last year. If this legislation had been force in the UK in 2012, Jimmy Savile’s crimes would still be secret.

Wootton says the allegations aired against him were untrue, denies doing anything criminal and feels his reputation has been unfairly tainted by the revelation he was under police investigation. His case is strengthened by the fact that two police forces decided not to charge him with any crime. Wootton says that he was set up and notes that no file was ever handed to police by the CPS.

But the case highlights the fact that we have a generally more cautious press, which is increasingly reluctant to put true stories into the public domain for fear of litigation.

The post Dan Wootton and the growing UK right to privacy explained appeared first on Press Gazette.