When historians come to consider when the Long Noughties ended, they may well choose 13 September, 2024. It marks the last episode of The Grand Tourthe post-Top Gear Amazon Prime series in which Jeremy Clarkson, James May and Richard Hammond picked up where they had left off on the BBC: more daft challenges, more mad stunts, more far-flung road trips and a lot more swaggering, giggling blokey banter. Some might call this last drive the end of an era – but really, this trio's era was over long ago.

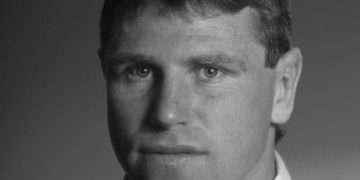

Things have changed since the three first came together Top Gear in 2002. Clarkson has turned into the savior of the British countryside on Clarkson's Farm. May has been allowed to tinker in his workshop like he always wanted, making his own gin and fixing toy trains on BBC Four's The Reassembler. Hammond, who was quite the little heartthrob back in the noughties with his bootcut jeans and spiky fringe, has managed to combine Alan Partridge's hair and country squire-lite wardrobe with David Brent's goatee. They are so far from fresh that it's easy to forget quite how much of a handbrake turn Top Gear felt when they first got behind the wheel.

The original Top Gear – which started in 1977 – had felt like a combination of Watchdogand someone from the council coming into your primary school to tell you how to cross the road. “Sue Baker reports on the value of air deflectors to save fuel, particularly as they relate to caravans,” read one tantalizing Radio Times preview. Another hard-hitting episode promised: “The MOT test continues to be controversial. Is the interpretation consistent from station to station and does the motorist get a fair deal?”

But the reboot was something altogether different. Out went sincere consumer advice; in came celebs doing hot laps in a mid-range saloon car. Top Gear wasn't for the humble motorist any more; it was for petrolheads, people who loved the “idea” of cars as much – possibly more – than actually driving them. Its mixture of daft challenges, international travel, and banter that danced merrily across the line of what was acceptable, made it genuinely fun to watch in a way that MOT comparisons stubbornly refused to. It's hard, for instance, to imagine Sue Baker uttering May's catchphrase: “Oh, cock.”

Ripping out nearly everything that would be of any practical use to someone driving a car, suddenly Top Gear became something you didn't need a driving license to like. The three hosts looked and sounded like overgrown boys having enormous fun amusing themselves, mainly because they were. I don't think it's overstating it to say that they were a model of what mid-Noughties Britain thought healthy men – and male friendship – ought to be: funny, and a bit mean, but big and strong enough to take it.

It became appointment viewing, and something half the world wanted to license its own version of. By the middle of the 2010s, between the international rights, the DVDs, the merch and the books, Top Gear was worth £50m a year to the BBC.

There was a whole Top Gear ethos, too. It's quite rare that a TV program – much less a Sunday night factual magazine show featuring three middle-aged men – creates its own worldview. But Top Gear had a personality. It liked rock music made between 1971 and 1983, it liked pre-distressed leather biker jackets, it fancied Gillian Anderson, and it thought this political correctness stuff was a load of bloody rubbish. For a while Clarkson, Hammond and May were King Dads, each representing a facet of the ultimate dad: Clarkson, the funniest man in the pub; May, the nerdish shed-dweller; Hammond, the dashing man about town.

Yet as things went on, a sense of drift set in. The globetrotting adventures got more and more ostentatious, the pranks more predictable, the Boomerish anti-PC grumbling metastasizing into something more horrible.

There was the 2014 furore over Clarkson reciting a version of “eeny meenie miney mo” which appeared to include the n-word, and a sly joke during a Thai road trip which used a slur against south-east Asian people. And casual homophobia became a running theme: a Jaguar XKRS would, Clarkson once joked, “get its tail out more readily than George Michael” – a jibe Michael himself called out.

It's fair to say the Angela Rippon or Tiff Needell years would not have troubled the Mexican ambassador to the UK. But these three did. “These offensive, xenophobic and humiliating remarks only serve to reinforce negative stereotypes and perpetuate prejudice against Mexico and its people,” Eduardo Medina-Mora Icaza said in 2011, complaining about an episode in which Hammond suggested a Mexican car would be “lazy, feckless , flatulent, overweight, leaning against a fence, asleep, looking at a cactus with a blanket with a hole in the middle on it as a coat”.

And yet none of it made any difference. The three amigos were, by the mid-2010s, pretty much untouchable, too big a success to rein in. “At that point,” May said later, “it was reckoned it had something like 350-360 million viewers.”

But, infamously, it all fell apart. In 2015, in one of the biggest BBC scandals of the era (and surely featuring the most euphemistic use of the word “fracas” in recent times) Clarkson punched producer Oisin Tymon and left him with a bloodied lip. An internal BBC inquiry found that Clarkson called him “lazy” and “Irish”, and Tymon won £100,000 in a discrimination and injury claim. Two weeks later Clarkson's BBC contract was terminated. First May, and then Hammond, announced they would walk away too. That quickly, one of the BBC's biggest properties essentially dissolved.

Immediately, it became clear that it was the three of them keeping the car show on the road. Top Gear continued with new presenters but started flailing, mixing and matching personalities hoping to evoke that old chemistry that cannot be forced. Yet during the mercifully brief Chris Evans debacle – he stepped aside after a single series – viewing figures dropped from 4.3 million to 2.8 million. The final series with Clarkson, Hammond and May averaged around 6.4 million.

Meanwhile, the original trio went over to Amazon. The Grand Tour started in 2016, but the car show no longer seemed enough to fuel them. Clarkson found a third act taking his Clarksoning to the country; May got to indulge his passion for fiddling about with things on charming BBC Four programmes; Richard Hammond's keeping busy with his Crazy Contraptions, Brain Reaction and Britain's Beautiful Rivers. Even The Grand Tour was at least as much a travel show by the end, taking you on a tour of cinematic landscapes you're unlikely ever to visit in your Vectra.

In fact, nobody makes car shows anymore. Is that because climate change is so much more urgent and frightening than it was in the Noughties, and the exotic sexiness of supercars has turned into something queasier? No – there are enough electric cars to fill a Top Gear series by now. Rather it's that the blokey bullishness that defined Top Gear and The Grand Tour has started to curdle.

Look anywhere on British TV and you'll notice the shift. Gogglebox, Taskmaster, Race Across the World, Mortimer and Whitehouse Gone Fishing – even Bake Offlong before them. Audiences prize earnestness, empathy, silliness and gentleness more than gunmetal gray and juvenile, laddish pratting about. And that shift has also slowly changed much of the bravado we were willing to ask of our TV stars. If you can be entertained by members of the public baking cakes in a tent, is it really necessary to ask them to put their lives at risk in a supercar?

That, in the end, was what brought Top Gear to a sharp halt. In December 2022 Andrew “Freddie” Flintoff's horror crash while filming for the show left him facially scarred and with broken ribs. It wasn't the first time. In 2006, Richard Hammond survived a horrible accident in a drag racer. “I was driving and then it was two weeks later and I was in Leeds,” he recalled a few months later. A tire blowout led to the car flipping and rolling off the runway at 288mph. Hammond was in a medically induced coma for a fortnight and had brain injuries. “There was a point when I couldn't daydream,” he said. “It was very frightening, very strange.”

It was awful. But Hammond was welcomed back with a display of sarcastic celebrations: fireworks and dancing girls met him as he walked into the studio for his first show after the crash. In 2022 things, though, were different, not least because Flintoff's physical injuries were so horrifying. “Genuinely should not be here after what happened,” he reflected a week later. The daredevil spirit that had defined Top Gear in its prime seemed so pointless. Leaving a national treasure with terrible injuries, smashing up his face and giving him nightmares and flashbacks, in the name of an eight-minute segment, was not worth it. Especially not when danger and adrenaline had become such an audience turn-off.

That danger and adrenaline, that trademark banter, lusting after unattainable motors, were what once revved Top Gear and The Grand Tour into turbo-hits. Now they're exactly what makes them feel so out of step. Even the fanfare for the three hosts' final ride has been muted – I suspect even they might be glad not to have to come up with any more pranks. Who's surprised Clarkson, Hammond and May are parking up? The car show has been running on fumes for years.

'The Grand Tour: One for the Road' is streaming on Prime Video